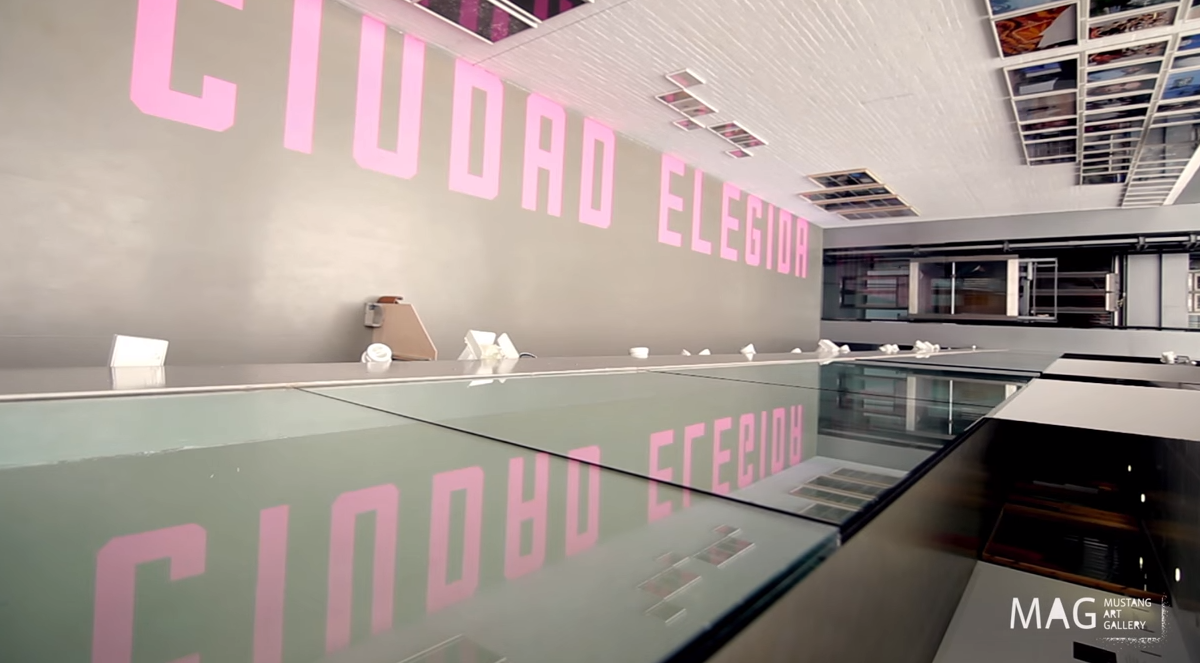

BLUE & WHITE

Reinaldo Thielemann Beca Puenting 2014 (UMH)

16th de July – 18th September 2015

Thieleman, the process as art

The artist measures time. He controls the process. When the signal is given, the bodies take up the anticipated space; they are spread over the fabric that has been chemically prepared beforehand and wait under the sun as witnesses of the procedure developing just as the artist has planned. The exposure to light ends and the first results can be seen. The water has just cleaned the surface full of white figures captured on deep blue. Young enthusiasts are amazed with this resulting image, a large flag with anonymities of bodies printed on it that can be identified nonetheless, due to both the exclusive trace of anatomical shapes and the trivial individualizing details: labels, hairs, decorations. They have formed part of a plastic art experience. They have been captured for eternity in a work of art, a gigantic blue print. Now, they are inside art, they belong to art. Not only has the model, the object to be depicted, been the main character, the author has also given it a certain creativity that has definitely had an influence on the subsequent piece.

The question then arises, what is the artwork? the outcome? the process? the original concept of the idea? The piece materializes as a result of a collective process insofar as the author needs the actual object that is being portrayed to cooperate, which in this case is the young volunteers who are acting under the orders of the author, who is like an orchestra conductor. Apart from the aesthetic experience, it could even be a sociological experiment to see how those involved in this game interact with each other, find their own space in the area of representation; they choose the posture and the part of the body that will be perpetuated forever. This has been the intention of Reinaldo Thielemann[1] to show digital generations, the remote techniques that were the origin of modern-day photography. In this way, the links between the past and the present are preserved. Nowadays, when it is so simple to capture images and it is even difficult to imagine a moment in history without them, Thielemann reminds us of how complicated it was to find the way to embody reality. In this case a copy of reality in white on blue. Indeed the blueprint that Thielemann uses in terms of its aesthetic appearance was used for a long time as a copying technique –blueprints– in the style of today’s photocopies. The artist works on a classic process in the search of a contemporary result, although the processes are also part of the work of art.

Photography was magic for the primitive cultures, it was not always seen positively, because it captured the spirit of the individual on a piece of paper. There is something of that in each image of ourselves that we immortalize. Infinite me’s –sometimes unrecognizable to oneself -, in infinite moments, have been gathered together in one instant. The image that we portray doesn’t have to match our inner image exactly. The inverted mirror. The nature of reality. We live in the era of the selfie, a period that promotes the mythification of the me, myself and I. The exaltation of the ego, multiplying the images and the thoughts of any individual by the endless social networks, eternalizing us in this way; seeing as none of us is going to be remembered in the aftermath, although we need to leave our mark on the earth. The invention of the selfie stick is the exacerbation of this current visual egocentrism, protecting personal space or avoiding the need to have to interact with another human being, whether it is because of distrust, to avoid having to feel indebted to a stranger or simply because you like to do it yourself.

In this panorama of selfies, when you don’t even have to ask someone else to take a photo of you anymore, Thielemann comes up with an ancient technique, a group vision, in which the photographer is the accomplice and the interested party of the model, of the resulting image being portrayed. Simplicity, the group, the personal relationships, the teamwork, the shared experience are recovered thanks to Thielemann, and in this unifying experience, surprisingly, the group enjoys, the participating individual enjoys, the viewer of the piece enjoys. Because the artwork is not an inert object that is meaningful in itself, it is interpreted and it takes part in it by contemplating it. The piece needs the interrelationship to actually make sense.

Natalia Molinos

[1] Winner of the 4th edition of the Puenting Grant for artistic professionalization awarded to a student of the Fine Arts Faculty of Altea (Universidad Miguel Hernández, Elche) by the ART MUSTANG.